Australian institutions’ financial ties to China mean ditching values.

The Chinese Communist Party’s attempted cover-up during the earliest stages of the coronavirus pandemic doomed the world to a historic public health disaster, one that would shatter the lives of billions of people. In the face of this catastrophe, both U.S. and European policymakers and thinkers have called for a reevaluation of their countries’ economic and political ties with this regime.

Sadly, the experience of critics like myself in Australia, a country far more reliant on Chinese economic ties than Europe or the United States, shows that decoupling will not be an easy task. After being an outspoken campus critic of Chinese state human rights abuses, I now face expulsion from the University of Queensland (UQ), where I am a fourth-year philosophy student, on the grounds that I “prejudiced” the university’s reputation by using my position as an elected student representative to express support for Hong Kong’s democratic protesters.

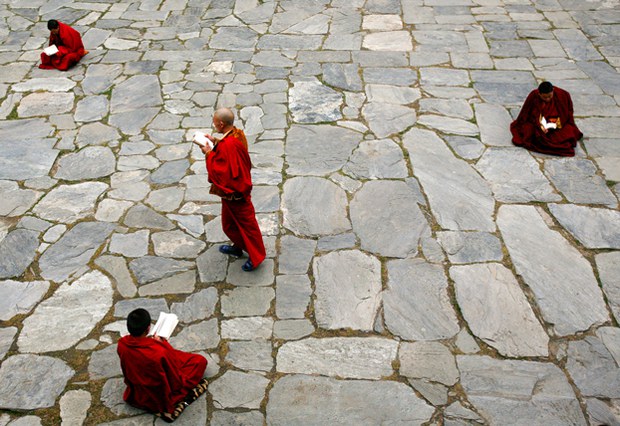

I am being threatened with this unprecedented move because of UQ’s particularly close relationship with the Chinese party-state; UQ enjoys perhaps the closest relationship of any university with the Chinese government in the Anglosphere. In addition to funding and controlling a Confucius Institute on campus, the Chinese government funds at least four accredited UQ courses that present a party-approved version of Chinese history to students, glossing over human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and mainland China.

In addition to these state-backed courses, the Chinese consul general in Brisbane, Xu Jie, serves as an honorary professor at the university. Vice Chancellor Peter Hoj, meanwhile, is a senior consultant to Hanban, the Chinese government organization that oversees Confucius Institutes worldwide, and received a 200,000 Australian dollar ($130,000) bonus from the university for bolstering ties with China. Confucius Institutes, educational institutes funded and run by the Chinese party-state, have come under intense scrutiny in recent years for “repeatedly straying from their publicly declared key task of providing Mandarin Chinese language training” in favor of disseminating Chinese state propaganda. In 2015, China’s then-vice premier awarded Hoj the Hanban “Outstanding Individual of the Year Award” for his “contribution, guidance and support to the UQ Confucius Institute and the Confucius Institute global network contributions to the promotion of the Confucius Institute network worldwide.” He only resigned from his position on the board of Hanban in December 2018 after being informed that his activities would have to be declared under Australia’s Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme.

Why has UQ fostered and developed these close links, even as the Chinese state has imprisoned over a million mostly Muslim ethnic minorities in camps, dispatched hundreds of thousands of them to coerced labor, and continued the harshest crackdown on freedom of speech, religion, and activism since 1989?

It is ultimately a cold, hard, brutal economic calculation, of a kind that many Australian and other Western institutions have made.

It is ultimately a cold, hard, brutal economic calculation, of a kind that many Australian and other Western institutions have made.

With nearly 10,000 students at UQ hailing from mainland China, the Chinese market is worth at least $150 million to the university in student fees each year. That market remains open only so long as UQ’s administration is willing to prostrate itself before Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. In a February 2020 meeting of the UQ Senate, where I serve as an elected student representative, the board approved paying Hoj a confidential six-figure bonus on top of his already eye-watering $1.2 million salary package. When I queried this, I was told he had met all his key performance indicators, one of which involved facilitating “engagement with China.”I threatened this engagement and these kinds of bonuses when I emerged last year as a vocal and prominent campus critic of UQ’s ties with the Chinese dictatorship. In July 2019, I led a peaceful campus sit-in calling for UQ to completely cut ties with the Chinese state until Tibetans were freed, Uighur detention camps were closed, and Hong Kongers were afforded greater democracy. Masked pro-CCP heavies violently attacked our rally, assaulting me and choke-slamming other pro-Hong Kong students to the ground. In the aftermath, I was named by Chinese state media and condemned as a “separatist” by Xu, the Brisbane consul general and UQ professor. After Xu’s statement, I was sent dozens of death threats. Some of the more vile promised to torture my family and rape my mother as I watched. I received anonymous, unsettling phone calls and letters in the mail and needed campus security to attend my classes.

UQ never dismissed Xu from his university post, even after he threatened my safety as a student. UQ put out a milquetoast statement affirming its commitment to “peaceful protest” but behind the scenes threatened to cancel my enrollment if I held another rally. When I requested to meet with the vice chancellor about what was happening, I was ignored and rebuffed. When I ran for the UQ Senate so he would have to meet with me, UQ officials recruited a pro-CCP candidate to run against me. When this pro-CCP candidate posted a statement on Chinese social media attacking me as “anti-China,” it went viral. Consequently, I was assaulted while campaigning, and threatening posters attacking me in Mandarin were put up on campus.

When I was elected despite all this, UQ stepped up its harassment. After posting an online satirical jab about the Confucius Institute’s ties to the Chinese government, UQ engaged a top-drawer Australian law firm, Clayton Utz, to intimidate and threaten me with a lawsuit. I was sent a letter by a partner at the firm instructing me that if I did not delete the post immediately, UQ reserved the right “to commence proceedings … to seek costs, including indemnity costs.” As a 20-year-old student, I had next to no ability to pay a billion-dollar institution like UQ “indemnity costs,” and they knew it. This was bullying and intimidation, plain and simple—an attempt to exploit the huge power imbalance that existed between UQ as an institution and me as an individual. I deleted the post.

It wasn’t enough for them. I was truly shocked when this April, just days before my publicly listed court proceedings against Xu in which I sought a protection order from the court for my own safety, UQ mailed me a remarkable 186-page confidential document outlining the case for my expulsion before a secret university tribunal with the power to deny me the ability to appear with legal representation. Alongside claims that my statements as a student representative in support of Hong Kong “prejudiced the reputation of the University” and forced Chinese students to drop out and thus cease paying university fees (the horror!), UQ listed absurdly trivial and petty matters in the case outlining my expulsion. One accusation leveled against me noted that I used a pen in a campus shop to write a note, only to return the pen to the shelf without paying.

Another allegation had it that I “bullied” UQ students when I responded to a group of people taunting me over the recent suicide of a close friend — a man on the opposite end of the political spectrum to me but who remained a dear mate — by responding to them with some colorful Australian English (as any grieving, hot-blooded 20-year-old would be wont to do). UQ knew of the suicide and knew that I was struggling yet chose to screen-cap my responses to those taunts to add to the case for my expulsion. The university decided to target me months ago and then compiled anything and everything it could use against me under the extremely broad terms of the Student Charter to attempt to expel me.

As I write, UQ seems determined to plow ahead with this politically motivated farce despite public outrage, condemnation by senior Australian government figures, and a 32,000-strong petition against my expulsion. The university doesn’t seem to care about the public relations disaster awaiting it, for the true audience for this move seems to be Beijing. In April, the Global Times, a Chinese state-controlled media outlet, put out an article calling for my expulsion. Quoting unnamed students at UQ, the state propaganda outlet asserted that there was broad student support for “expelling or punishing an anti-China rioter who has allegedly disrupted campus order.” Please take a moment to reflect on the insanity of this. A nuclear-armed superpower used its state-controlled media to call for the expulsion of a 20-year-old Australian student critic. If this type of interference is allowed in Australian universities, I won’t be the last student to face this threat.

Ultimately, my ability to complete my education at my hometown university in Australia is up in the air due to my political activities critical of the Chinese government’s human rights abuses. If I am expelled, I fear the terrifying signal it would send to students across the country. On reading the entire document, Clive Hamilton, a noted expert on CCP influence operations in Australia, wrote to me: “Most of the allegations are trivial; some are risible. In the context of the University’s documented discomfort with your political activism—especially your highlighting of links between the University, its Vice-Chancellor and various arms of the Chinese Communist Party—I can only read the threat of expulsion as an attempt to silence legitimate political activism on the campus.”

He’s right—it’s an attempt to intimidate students into self-censorship. Already, I know dozens of students at UQ who have told me they cannot join me in my activism for fear of university reprisals. If I lose the case and have my enrollment voided, who will dare speak out again?