By Matthias Williams, Reuters, Feb 16, 2012

The plight of Tibetans has deteriorated since a wave of deadly protests shook the region in 2008, as soldiers, spies and constant checkpoints put the Chinese region into a “lockdown”, the Tibetan prime minister-in-exile said.

Relations between exiled Tibetan leaders and Beijing had also deteriorated in the past four years as the Chinese government shunned talks with Tibetan envoys, Lobsang Sangay told Reuters in an interview on Thursday.

Riots killed at least 19 people throughout Tibetan parts of China in 2008, prompting the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, to call life in the region “hell on earth”.

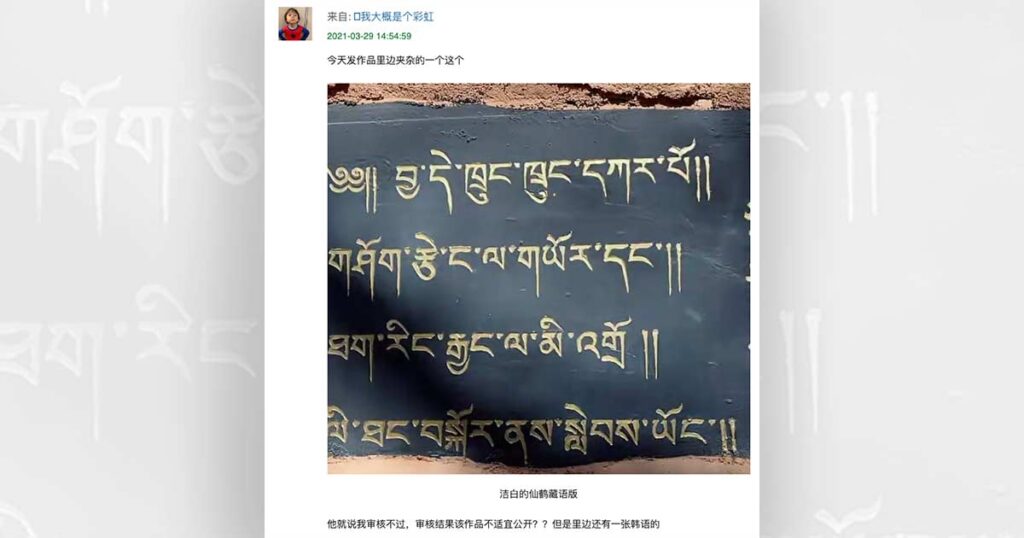

Beijing has tightened its grip on what it calls the Tibet Autonomous Region since then, flooding the area with soldiers and non-Tibetan Chinese, and squeezing the job prospects and freedom of expression of the local population, Sangay said.

In the past year, Chinese authorities have grappled with a spate of self-immolations protesting the Tibetans’ plight. Beijing has called the deaths acts of terrorism and accused the Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in India, of fomenting unrest.

“What’s happening is a lockdown of Tibet. And it’s very, very worrisome,” Sangay said. “They really don’t want the outside world to know what’s happening inside Tibet.

China has ruled Tibet since Communist troops marched in in 1950. It rejects criticism that it is eroding Tibetan culture and faith, saying its rule has ended serfdom and brought development to a backward region.

The Dalai Lama fled Tibet in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese rule.

“What you see is more Chinese moving in, more jobs being taken over, more presence in the administration, more military presence and more discrimination,” Sangay said.

He spoke to Reuters in a sparse meeting room at an office of the Dalai Lama in New Delhi. On the same morning, a short drive away, dozens of police officers dragged crying and screaming Tibetan protesters away from the manicured laws outside the Chinese embassy, bundling them into vans.

The demonstration, by a few dozen Tibetan students, was short-lived. Cries of “free Tibet” and “we want justice” quickly fell silent and traffic noises picked up again as the protesters were taken away.

‘MORE CRACKDOWN’

Tension has risen in Tibetan parts of China since January. Since last March more than a dozen Tibetans are believed to have died by setting themselves on fire. The Dalai Lama has blamed the self-immolations on “cultural genocide” by the Chinese.

Advocacy groups fear the burnings will continue or accelerate before the Tibetan new year, which begins on February 22. Sangay denied stoking the self-immolations but hinted at the prospect of further unrest during the new year, where he has asked Tibetans to observe spiritual rituals rather than party.

“So you will go to the monastery to pray. Now if that is seen as a gathering and a protest, then you are looking at a very, very worrisome scenario,” Sangay said.

Foreign journalists, academics and even domestic tourists had been barred or discouraged from entering Tibetan areas, Sangay said. Internet and phone services had been restricted and military camps set up outside major monasteries, he added.

“It looks like the Chinese government is preparing for more crackdown, (rather) than trying to really understand the grievances of the Tibetan people,” he said.

A Harvard law scholar, the 43-year-old Sangay is now the exiled Tibetans’ highest ranking political leader after the Dalai Lama retired from political life last year. In May, China effectively ruled out dialogue with Sangay’s government, saying it would only meet with representatives of the Dalai Lama.

“The Chinese government has not received our envoys since January 2010,” Sangay said.

The Dalai Lama still casts a long shadow over policy-making, and many Tibetans worry what shape their struggle for greater autonomy will take once the charismatic leader, with his message of non-violence, dies.

“(It’s a) lot harder because before, many decisions you make, you have to seek his endorsement. Then you go to the Tibetan people and say I have the endorsement of His Holiness. Then you are shielded by that endorsement,” Sangay said.

“Now, the final decision is yours. Then if something goes wrong, obviously you’ll be criticised.”